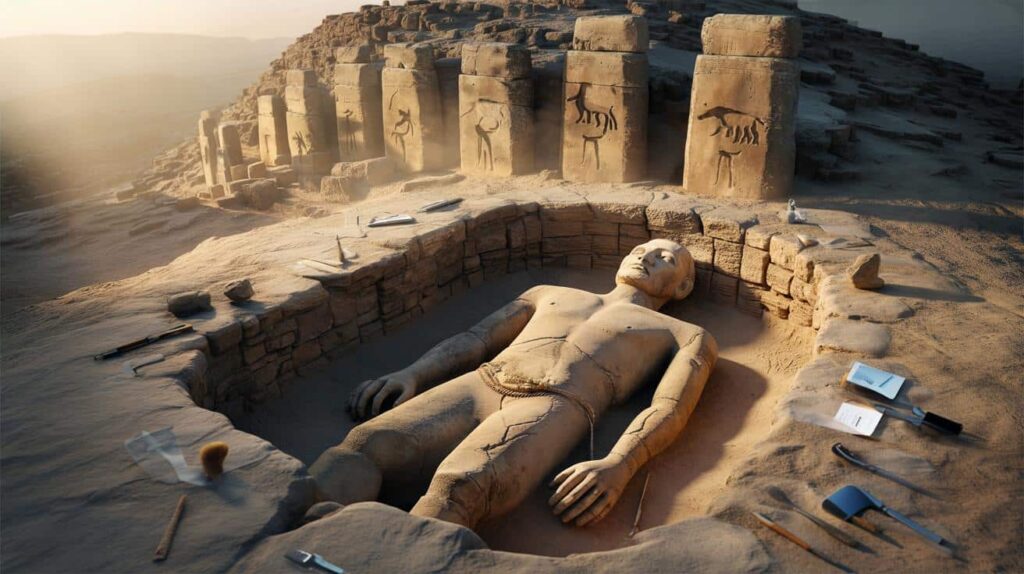

Archaeologists working at Göbekli Tepe say a human-shaped statue, hidden inside a 12,000-year-old structure, could force a rethink of how and why civilisation began.

A buried figure in a prehistoric wall

The statue was unearthed at Göbekli Tepe, about 15 kilometres from the city of Şanlıurfa in southeastern Turkey. The site dates to around 9600 BC and is widely regarded as the oldest known monumental ritual complex on Earth.

During a carefully planned excavation, researchers found the sculpture inserted horizontally into a cavity inside a stone wall. It was not lying there by chance. Its position suggests a deliberate act linked to ritual or belief.

A 12,000-year-old human figure, purposefully built into a sacred wall, places belief at the heart of early settled life.

The excavation is led by Professor Necmi Karul from Istanbul University, under the wider Taş Tepeler (“stone hills”) project. This programme brings together 36 scientific institutions and around 220 specialists across ten Neolithic sites in southeastern Anatolia.

The find has not yet been fully published in an academic journal. Conservation work is still underway, and detailed images are being withheld to protect the object during cleaning and analysis. The Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism is closely involved, signalling how much is at stake scientifically and politically.

Göbekli Tepe: not a village, but a ritual machine

Unlike later Neolithic sites, Göbekli Tepe does not show signs of everyday living. There are no hearths, houses or burials in the excavated areas. Instead, the hill is dominated by circular or oval structures defined by towering T-shaped limestone pillars, some up to six metres high and weighing about 20 tonnes.

These circles appear to have been gathering places rather than homes. Many of the pillars are carved with animals — snakes, foxes, boars, birds of prey — and abstract symbols. The new statue adds a human presence directly into the architecture.

The location of the figure, locked into the masonry of a chamber wall, suggests that architecture and ritual were fused. The building was not just a backdrop to ceremonies. The walls themselves carried messages and meanings, turning stone into a permanent record of shared beliefs.

At Göbekli Tepe, stone walls acted like a collective memory device, preserving stories and symbols long after the people moved on.

A rare full human in a world of animals

What makes this statue especially striking is that it seems to represent a complete human figure. At Göbekli Tepe, full human depictions are surprisingly scarce. Most carved imagery is animal-based, or shows stylised human arms and hands on the T-shaped pillars rather than full bodies.

In that context, a full human-shaped statue, carefully sealed inside a wall, stands out. Researchers suspect it was a votive offering — something placed in the structure as a meaningful sacrifice or dedication. Similar, though less complete, human figures have appeared at nearby Karahantepe, but the Göbekli Tepe example seems more integrated into the building itself.

The piece is dated to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA), around 9600–8800 BC. Communities of this era had not yet adopted pottery or fully domesticated animals. Many people still hunted and gathered their food, yet they were already building vast stone enclosures that required coordination, time and shared purpose.

Why archaeologists are so interested in one statue

For specialists, the statue offers a rare window into how these people imagined human identity. Was the figure an ancestor, a mythical hero, or a supernatural being? Was it someone specific, or a type representing humanity as a whole?

By examining the proportions, style and any clothing or adornment carved onto the statue, researchers hope to tease apart how early communities saw themselves in relation to the spirits, animals and landscapes around them.

- Pose and orientation: can hint at ritual gestures or roles.

- Facial features: may show emotion, status or stylisation.

- Body details: belts, necklaces or weapons could signal rank or mythic attributes.

Rewriting the timeline of civilisation

For much of the twentieth century, a simple story dominated school textbooks: first came agriculture, then permanent villages, then religion and large monuments. Göbekli Tepe has been slowly dismantling that sequence.

The site is older than the first known farming villages in the region. Yet it already has monumental structures that would have required planning, labour organisation and some form of leadership or shared decision-making.

The newly found statue pushes that point further. It suggests that shared beliefs and complex rituals were not side-effects of settled life, but may have been the trigger. People might have gathered at certain places for ceremonies, feasts and seasonal rituals. To sustain those gatherings, they needed reliable food supplies, which in turn nudged them towards cultivating plants and managing animals.

Instead of “farming created temples,” Göbekli Tepe hints that “temples created the need for farming.”

From roaming bands to rooted communities

Karul and his colleagues argue that myths, ceremonies and collective offerings acted as glue. They bound scattered groups into something like a community, even before permanent villages took shape.

If that interpretation is right, early civilisation was built as much from stories and symbols as from seeds and stone tools. Religion, or at least shared ritual behaviour, may have been a driving force in pushing humans to settle down, cooperate and build lasting structures.

| Stage | Older model | Emerging view from Göbekli Tepe |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Invention of agriculture | Seasonal gatherings and shared rituals |

| 2 | Permanent villages | Construction of ritual enclosures |

| 3 | Temples and organised religion | Pressure for stable food, leading to early farming |

How the project is run on the ground

The Taş Tepeler initiative treats the region as a connected cultural landscape rather than isolated sites. Göbekli Tepe, Karahantepe and other hills are seen as parts of one broader experiment in early monument building.

At Göbekli Tepe, recent work has included restoring “Structure C”, one of the largest stone circles. Archaeologists have repositioned pillars where possible and reinforced walls with a mortar that includes goat hair, mimicking Neolithic techniques recorded in the area.

Geophysical surveys — essentially underground scans using instruments — guide future excavations. This limits random digging and helps protect fragile layers. When a feature like the statue appears, specialists in stone conservation move in quickly. Temperature, humidity and even the kind of tools used can affect whether such an object survives intact or crumbles on contact with air.

Why human statues matter for ordinary readers

For people outside archaeology, a single statue might sound like a small detail. Yet objects like this can shift big debates about human history. They tie abstract theories about belief and society to something tangible and personal.

Seeing a 12,000-year-old human figure carved in stone can change how we think about those early people. They were not simply “primitive” bands chasing herds. They invested time and scarce resources into symbols that outlasted individual lives. That choice speaks of values, priorities and fears that feel surprisingly close to our own.

There are also present-day implications. Sites like Göbekli Tepe sit at the junction of science, tourism and national pride. Turkey has been showcasing objects from Şanlıurfa in major exhibitions abroad, including Rome in 2023 and a planned show in Berlin in 2026. These efforts turn local finds into global reference points for human origins.

Key terms and ideas in plain language

The story of this statue includes technical phrases that can sound opaque. Two are especially useful:

- Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA): a label for the earliest known settled communities in the Near East, before people used fired clay pots. They built in stone, used stone tools and relied largely on wild plants and animals, even as they experimented with cultivation.

- Votive offering: an object placed somewhere sacred — a wall cavity, a pit, a shrine — as a gift or pledge. The giver expected no return in a transactional sense. The act itself was meant to maintain relationships with gods, ancestors or spirits.

Thinking in those terms helps frame the statue not just as ancient art, but as an active part of a ritual act. Some researchers imagine the scene: a group gathers, perhaps during a seasonal event. The statue is displayed, words or chants are spoken, then it is sealed into the wall. From that point on, anyone using the building knows a human presence lies inside the stone, unseen but not forgotten.

That kind of mental experiment — reconstructing how a ritual might have unfolded — can guide excavations. If walls contained offerings, floors might hide others. If human figures appear in one structure, they might cluster in certain areas or orientations. Each new find then tests these scenarios, tightening or challenging the story.

The 12,000-year-old statue at Göbekli Tepe now sits at the centre of such debates. As conservation teams restore it and analysts study every mark on its surface, the figure in the wall is quietly reshaping how we think about the birth of civilisation itself.