The first thing you notice is the silence. Forty meters down in the black water off Sulawesi, the world narrows to the hiss of your regulator and the faint glow of your dive light cutting into a velvet wall of night. Then something moves at the edge of the beam. Not fast. Not panicked. Just a slow, deliberate roll of thick, armored flesh, as if a fragment of a prehistoric painting had just shrugged and come to life.

The Indonesian guide squeezes the photographer’s arm so hard his dive computer beeps.

The creature turns, eyes shining an odd metallic blue, jaws edged with ivory teeth that don’t quite look like they belong in this century.

One click of the shutter.

And a legend finally steps into the light.

A ghost from the age of dinosaurs, suddenly in HD

For marine biologists glued to screens in Jakarta, Paris and Cape Town this week, the new photos from that night dive felt like a slap in the face. On their monitors: the first crisp, color images of what local Indonesian fishers have whispered about for decades – a hulking, blue-gray predator they call “ikan batu hidup”, the living rock fish.

What the world is now arguing over is whether that “rock” might actually be a living fossil, a deep-sea hunter whose bloodline stretches back to before the first birds took flight.

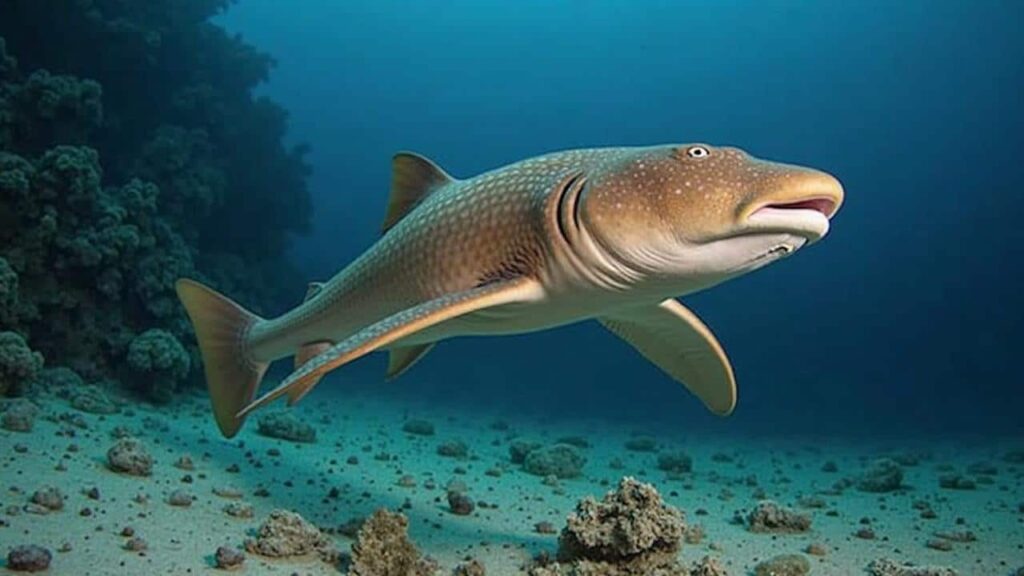

The photos, shot off North Sulawesi at around 220 meters during a mixed-gas technical dive, are unsettlingly sharp. You see thick, lobe-like fins that look eerily like limbs. A heavy, scale-plated body tapering to a powerful tail. Eyes that catch the flash and glow like antique glass marbles.

Within hours of the divers posting a teaser frame to Instagram, marine Twitter exploded. Some shouted “new coelacanth species” before the coffee even brewed. Others, more cautious, compared body proportions, fin rays and that strange pattern of white spots to known Indonesian coelacanths and found…just enough differences to fuel an all-out scientific brawl.

This is where the debate gets hotter than a surface current in August. One camp argues that we’re simply seeing an under-sampled population of the known Indonesian coelacanth, Latimeria menadoensis, caught in better light than usual. Another points to the jawline, the thicker cranial ridge, and that spine-like dorsal fin as evidence of a sister lineage that split off millions of years ago and quietly survived in the Sulawesi trenches.

The deeper, slightly uncomfortable question is this: if such a large, unmistakable predator can still surprise us in 2026, how much do we really know about the deep sea’s living fossils at all?

How a handful of divers cracked open a scientific mystery

The dive itself was almost canceled. Strong afternoon winds had chopped the surface into a gray mess, tangling lines and rattling nerves. One of the team’s rebreathers was acting up. The sort of day when most photographers admit defeat and go edit old footage on their laptops.

But the Indonesian guide, a wiry man named Riko who’d grown up on these waters, quietly insisted on one more drop along a barely-mapped submarine canyon that local fishers avoided at night. “Big old fish here,” he said, tapping the chart with a calloused finger. “They watch you.”

At 180 meters the water went from dark blue to pure ink. The team inched down a steep rock wall riddled with caves, lights sweeping over shy crustaceans and sleeping reef sharks. Then the lead diver’s beam stopped. Sitting motionless in a crevice, head down, was the shape that would ignite a thousand think pieces: stout body, thick fins drooping like arms, tail coiled.

They hovered, counting seconds, fighting buoyancy, while the photographer nudged his strobes into place with gloved fingers that were starting to go numb. The animal rose, rotated slowly towards them, and – in a moment that now loops endlessly on social media – opened that impossible mouth in what looks disturbingly like a yawn.

From a scientific point of view, this is the worst and best case rolled into one. Best, because we finally have clear evidence that a large population of these animals is using Indonesian canyons more frequently than old records suggested. Worst, because photos alone are a nightmare for taxonomists. No tissue samples. No DNA. Just pixels and heated arguments over scale counts and head shape.

Yet those same images are pushing a fresh, uncomfortable logic: maybe our model of “rare, fragile living fossils hiding in small pockets” is wrong. Maybe some of these lineages are thriving right under busy shipping lanes, simply deep enough and strange enough that we’ve trained ourselves not to look.

Watching the debate unfold – and what it reveals about us

Behind the glossy headlines about “Jurassic fish” and “time-traveling predator”, there’s a more human story unfolding in labs and group chats. Young Indonesian researchers, many of whom grew up hearing village tales about monster fish stealing nets, are suddenly center stage. They’re fielding interview requests, fronting press conferences, and trying to keep the focus on long-term monitoring rather than viral fame.

Their first move was simple but smart: lock down the raw files, log metadata carefully, and invite independent experts to Jakarta to review the material on-site instead of screenshot-sniping online.

That’s not usually how these stories go. We’ve all been there, that moment when a wild clip drops into your feed and the hot takes start flying, while the people who actually shot it are still decompressing. This time, the dive team publicly admitted what many are too proud to say: they don’t fully know what they filmed.

Let’s be honest: nobody really does this every single day. Sharing a potentially history-making discovery while openly saying “we need help” runs against the grain of the attention economy. Yet that humility – from the divers and the scientists they called first – is slowly reshaping the tone of the global conversation.

Some of the sharpest words have come from people who’ve waited their entire careers to see images like these.

“Everyone wants a headline that screams ‘new species’,” says Dr. Lila Santoso, a deep-sea ecologist at Indonesia’s National Research and Innovation Agency. “But what we really have is a living question mark. And questions are much harder to fund than monsters.”

Inside her team’s office, someone has scrawled three blunt priorities on a whiteboard, now circulating widely online as a kind of reality-check mantra:

- Get more images. No touching, no chasing.

- Work with local fishers, not around them.

- Protect the canyon first, name the fish later.

*The plain truth hidden in that list is that the story isn’t just about a fossil fish; it’s about whether we can resist turning every mystery into clickbait before we even understand what’s at stake.*

What this “living fossil” really asks of us

Step back for a second from the noise and you’re left with a strangely intimate image: a small group of humans hanging in the dark, breathing borrowed air, face-to-face with an animal whose ancestors watched continents drift apart. That meeting, frozen now in ultra-high-definition, says as much about our species as it does about theirs.

We’re compelled to label, to own, to announce. Yet the deep sea doesn’t care about our timelines or our trending tags. It just keeps rolling out these slow, patient survivors, waiting to see how we’ll respond this time.

Some readers will look at the photos and see proof that wild things endure, no matter how hard we push the planet. Others will see a warning: if something this big can hide from us for so long, what else are we missing while we argue about details in the comments section.

Maybe that’s the quiet power of this Indonesian predator. It forces us to confront both our ignorance and our curiosity in the same breath. It dares us to ask fewer, louder questions about monsters and more, quieter questions about coexistence, attention and restraint.

No one knows yet if the genetic tests will confirm a “new” species or just expand the family tree of a line we already thought we understood. What we do know is that a canyon once dismissed as another patch of deep blue on a chart is now pulsing with new significance.

Somewhere down there tonight, a thick-finned hunter is cruising between rocks, utterly unaware that its unhurried swim has triggered grant proposals, ethical debates and late-night arguments in faraway kitchens. The real cliffhanger isn’t whether we’ll see it again. It’s what we’ll choose to do before we do.

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Living fossil in focus | First detailed photos of a legendary Indonesian deep-sea predator ignite debate over a possible new coelacanth lineage | Gives a rare, front-row glimpse into how scientific discoveries are born in real time |

| Divers as catalysts | A small, mixed team of local guides and technical divers revealed a hidden canyon ecosystem off Sulawesi | Shows how ordinary expeditions can unexpectedly change what we think we know about the planet |

| From viral hype to long-term stakes | Researchers push for protection, more data, and collaboration with local communities before chasing names and headlines | Helps readers see beyond clickbait and understand what’s actually at risk in the deep sea |

FAQ:

- Is this really a “new” species?Right now, no one can say for sure. The body shape and fin structures look different enough from known Indonesian coelacanths to raise eyebrows, but without DNA or a full physical examination, scientists are calling it a “candidate lineage” rather than a confirmed new species.

- Where exactly was the predator filmed?The dive took place off North Sulawesi, Indonesia, along a steep submarine canyon dropping beyond 200 meters. The precise coordinates are being kept confidential by the research team to avoid a rush of unregulated expeditions into a fragile habitat.

- Is the animal dangerous to humans?There’s no evidence that this predator poses any direct threat to divers or swimmers. Encounters so far show a slow, cautious animal that prefers to stay near rocky crevices at depths most recreational divers never reach.

- Why are photos such a big deal for scientists?Clear, well-lit images from known depths and locations help experts compare anatomy with museum specimens and historical records. They’re not as definitive as DNA, but they can reveal differences in fins, scales and body proportions that point to hidden diversity.

- Can the public help with this discovery?Indirectly, yes. Supporting organizations that fund deep-sea research, resisting the urge to harass or disturb wildlife for content, and amplifying voices from Indonesian scientists and coastal communities all shape what happens next far more than a single viral share.