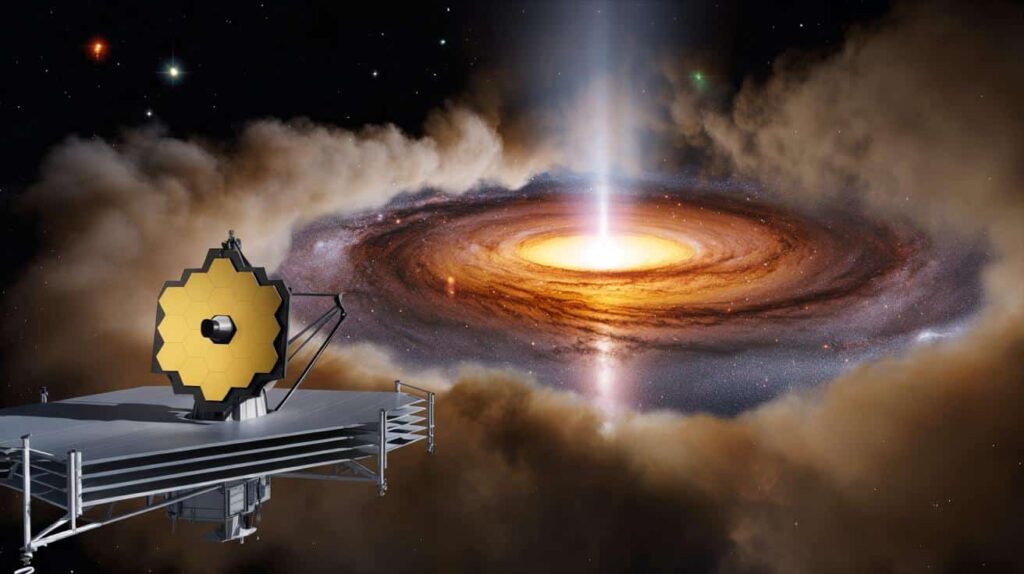

Now, the James Webb Space Telescope has finally pulled back that veil, revealing how a ravenous supermassive black hole is being fed inside one of the most active galaxies in our cosmic neighbourhood.

The galaxy next door that keeps astronomers guessing

The target of this new observation is the Circinus Galaxy, also called the Compass Galaxy, just 13 million light-years from Earth. That distance makes it relatively close on a cosmic scale, almost a neighbour compared with faraway galaxies seen by Webb.

For years, Circinus has been known as a busy, restless system. Stars form there at a rapid pace, and the central region shines strongly in infrared light. Yet for observers on Earth, the galaxy is tricky to study. It lies very close to the plane of our own Milky Way, where clouds of gas, dust and foreground stars crowd the view.

Psychology explains what it says about you if you feel emotionally reactive but logically calm

Psychology explains what it says about you if you feel emotionally reactive but logically calm

Even powerful ground-based telescopes struggle with this clutter. Circinus can be spotted with good amateur equipment under dark skies, but its core remains blurred and obscured. Earlier images from the Hubble Space Telescope already hinted at something unusual: a bright patch of infrared radiation close to the galaxy’s centre, where a supermassive black hole sits.

That infrared glow was a clue that something energetic was happening near the black hole, but not what kind of activity was taking place.

For a long time, one popular idea suggested that hot gas was being blasted out from the black hole, driven by powerful jets or winds. Webb’s new data now flips that picture on its head.

A dusty “doughnut” feeding a hungry black hole

The new study, based on James Webb’s infrared observations and published in the journal Nature Communications, shows that most of the radiation is not due to material being expelled from the black hole. It is mainly coming from material falling toward it.

Webb’s sharp vision reveals a thick ring of dust and gas wrapped around the central black hole. Astronomers call this structure a “dusty torus”, but the team behind the study often compares it to a doughnut. The black hole sits in the middle, while the ring acts as both a shield and a fuel reservoir.

As this dusty doughnut slowly feeds the black hole, gas and dust spiral inward. Friction and gravity heat the material to extreme temperatures, creating a glowing disc of infalling matter called an accretion disc.

The observations show that about 87% of the infrared radiation seen from the galaxy’s centre comes from this hot, feeding dust cloud surrounding the black hole.

Only about 1% of the infrared energy appears to be linked to material actually thrown out by the black hole, far less than previous data had suggested. The remaining 12% comes from regions farther out in the galaxy that earlier telescopes simply could not isolate.

Why the centre was so hard to read

At the heart of Circinus, two bright sources compete for attention: the black hole’s feeding zone and the dense crowd of stars nearby. From Earth, those light sources blur together, and interstellar dust blocks much of the view. That combination has made detailed analysis difficult for decades.

When matter swirls into the black hole’s accretion disc, it shines so strongly that it tends to hide everything else. For shorter-wavelength telescopes like Hubble, this glare is almost blinding. The glow from young stars and the scattered light from dust only add to the mess.

James Webb can see in the infrared, which partly solves the problem. Infrared light passes more easily through dust, allowing astronomers to look deeper into the galaxy’s core. But even Webb needed an extra trick to separate the bright central glow from the surrounding starlight.

Webb’s interferometer trick pays off

To sharpen its view, Webb used a technique familiar to optical engineers: interferometry. One of its instruments, NIRISS (Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph), can be operated as a tiny interferometer. In this mode, it combines light in such a way that intense glare from bright sources is filtered out.

For the first time, Webb’s interferometric capability was used to study an object beyond the Milky Way, with Circinus as the test case.

This configuration allowed scientists to “mask” some of the overwhelming starlight and isolate the faint signatures of the dusty torus. Crucially, the trick reduced artefacts – those false patterns and streaks that sometimes appear in very bright images – giving a much cleaner view of the galaxy’s centre than previous telescopes could manage.

With this clearer picture, researchers were able to disentangle how much radiation comes from each part of the system and match those numbers against theoretical models of how active galactic nuclei behave.

What the numbers say

- 87% of the infrared energy: from the thick dust cloud, or torus, feeding the supermassive black hole.

- 1%: from material actually being ejected by the central engine.

- 12%: from more distant regions in the galaxy, previously blended into the central glow.

These proportions suggest that Circinus hosts a very actively accreting black hole, but the majority of the heat and light we see is wrapped up in the immediate surroundings, not in dramatic outflows. The galaxy is less of a cosmic blowtorch, more of a heavily shrouded furnace.

Why Circinus matters for black hole physics

Galaxies like Circinus are valuable laboratories. They sit close enough that telescopes can pick out fine details, and yet their central engines resemble those seen in much more distant, brighter active galaxies and quasars.

By confirming the presence of a dusty torus in Circinus, Webb gives weight to a long-standing “unified model” of active galactic nuclei. In this framework, many different-looking active galaxies are actually the same type of object seen from different viewing angles and through different layers of dust.

Circinus shows that a thick ring of dust can both hide and feed a black hole, changing how we interpret its brightness from Earth.

This has practical consequences. Astronomers rely on the light from these objects to estimate how quickly black holes grow, how they affect their host galaxies, and how common they are over cosmic time. If dust hides much of that activity, earlier estimates may need adjustment.

What this means for future Webb projects

The successful use of NIRISS as an interferometer on Circinus opens the door to similar campaigns on other galaxies. Teams are already planning follow-up studies targeting different types of active nuclei, from relatively quiet central black holes to more ferocious quasars.

By applying the same method, Webb can map how dusty tori change with black hole mass, fuel supply and galaxy environment. That, in turn, will help trace the life cycle of galaxies: when they feed their central black holes, when they shut them down, and how these processes interact with bursts of star formation.

Key terms that help make sense of the result

For readers less familiar with the jargon, a few concepts sit at the heart of this story:

| Term | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Light-year | The distance light travels in one year, about 9.46 trillion kilometres. Circinus is 13 million light-years away. |

| Supermassive black hole | A black hole with millions or billions of times the Sun’s mass, usually found at the centre of a galaxy. |

| Accretion disc | A rotating disc of hot gas and dust spiralling into a black hole, heated so much that it emits intense radiation. |

| Dusty torus | A thick, doughnut-shaped ring of dust and gas around the accretion disc that can block and re-radiate light. |

| Infrared radiation | Light with longer wavelengths than visible red light; it reveals warm dust that optical telescopes often miss. |

Thinking of the system as household plumbing gives a rough mental image. The galaxy’s gas and dust form a large reservoir. The torus is like a ring-shaped funnel. The accretion disc resembles the swirling water near a drain. The black hole is the sinkhole where everything disappears, and the infrared light is the heat given off by the turbulent flow.

From simulations to sound and classroom use

Nasa teams and university groups often run computer simulations of matter falling into black holes like the one in Circinus. These models show how gas clumps, heats up and sometimes shoots out in narrow jets. Comparing Webb’s data to these virtual black holes lets researchers test which models best match reality.

Teachers and communicators have also turned black hole data into sound, a technique called sonification. Variations in brightness or X-ray flares are mapped to pitch and rhythm, creating eerie audio tracks. Although the new Circinus results are in the infrared, the same approach could translate the feeding pattern of its black hole into something you can hear, not just see.

For keen amateurs, Circinus offers a practical target too. While no backyard telescope will show the dusty doughnut itself, observers under southern skies can try to track down the galaxy as a faint patch near the constellation Circinus. Future citizen science projects may invite volunteers to compare Webb-based models with visible-light images, helping refine how dust affects what small telescopes record.

The broader message from Webb’s latest result is that even familiar nearby galaxies still hold surprises once the right instruments peel back the layers of dust. As more galaxies get the same treatment, our picture of how black holes grow at the centres of galaxies is likely to shift again.