On a small town street somewhere in Texas, a mother was already rehearsing the moment on her phone. “Three minutes,” she whispered to her kids, trying to steady the video as the daylight dimmed like someone sliding a dimmer switch. Dogs began to bark. A car alarm went off for no reason anyone could explain. For a heartbeat, the town felt like it was holding its breath together.

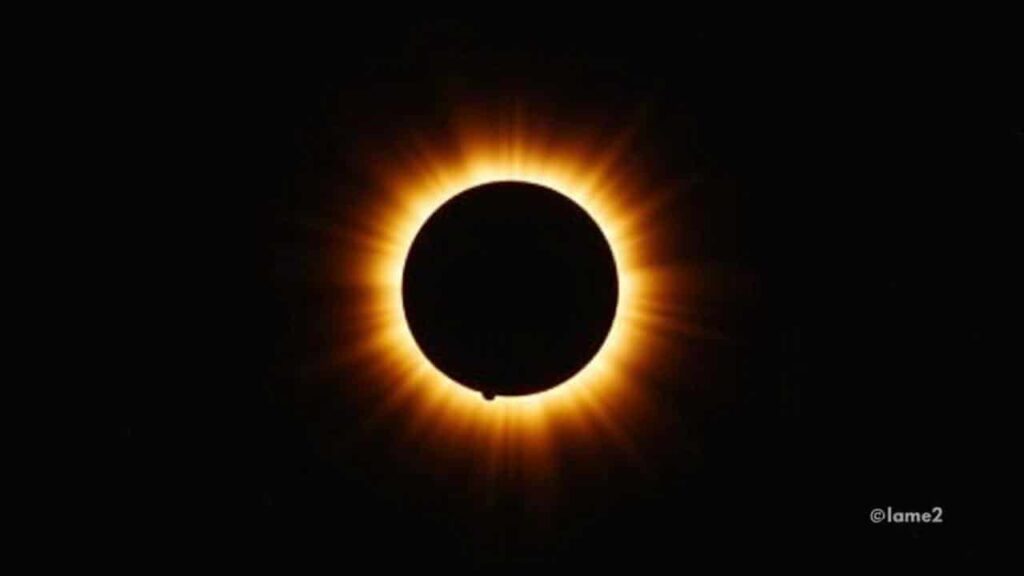

The sun shrank to a thin ring of fire, and day pretended to be night.

Next year, astronomers say, this feeling will last even longer. A total solar eclipse, the longest of the century, will slice across the sky – an almost unbelievable piece of cosmic theater.

Some call it a miracle of geometry. Others, a dangerous distraction from everything burning down here on Earth.

Both might be true.

When the sky steals the spotlight from everything else

For a few rare minutes, the world becomes a weird kind of cinema. Streetlights flicker on in the middle of the day. Birds lose their script and start acting like it’s sunset. People who haven’t looked up from their phones in months suddenly stand in parking lots, necks craned, quietly waiting.

Astronomers say this upcoming eclipse will stretch totality past the 7‑minute mark in some locations, the longest such event of the 21st century. That’s a lifetime in eclipse terms. Long enough to feel the temperature drop on your skin. Long enough to feel a shiver that has nothing to do with the weather.

In 2017, the last huge “Great American Eclipse” turned sleepy towns into pop-up festivals. In Oregon, a farmer who usually rents out hay balers rented out patches of his field for $300 a night instead. In Missouri, a diner ran out of eggs by 9 a.m. because people were driving for hours just for a few seconds of totality and a plate of pancakes.

One small Kentucky town of 2,000 residents saw its population swell to 25,000 for a single day. Traffic backed up for miles. But strangers shared eclipse glasses at gas stations like they were rare currency. People cried. Adults hugged like kids at a fireworks show. The sun disappeared, and thousands of phones pointed up at once, like a digital forest of worship.

Astronomers are already calling this new event **a once‑in‑a‑lifetime alignment**. The path of totality will cross densely populated regions, which means tens of millions of people could step outside and watch day fold into a brief, trembling night.

Yet the louder the excitement gets, the sharper another question becomes: at a time of climate anxiety, war, inflation and collapsing attention spans, why does this cosmic moment feel so urgent?

Some activists argue that eclipses and similar “spectacle news” soak up coverage that could go to more pressing stories. Others counter that humankind needs shared awe the way lungs need air. The sky, they say, doesn’t erase our problems. It throws them into bolder relief.

How to stare at the sun without burning your future

First, the boring but non‑negotiable bit: you don’t look straight at the sun without proper protection. Not during a partial eclipse. Not “just for a second.” Not with two pairs of sunglasses stacked on your nose.

Safe viewing means ISO‑certified eclipse glasses or a proper solar filter over binoculars or telescopes. Every astronomy group in the world repeats this because eye damage from eclipses is silent and permanent. No pain, no warning, just a burnt patch in your vision that doesn’t come back.

If you don’t have glasses, you can still watch the event indirectly. Make a pinhole projector from cardboard, or let sunlight filter through leaves and watch dozens of tiny crescent suns dance on the pavement. It’s low-tech, weirdly poetic, and kids love it.

Let’s be honest: nobody really does this every single day. We don’t step outside at noon to admire the sun or time the birds. We scroll, we rush, we reply to messages half a beat too late, feeling guilty for not doing more, faster.

So when people tell you an eclipse is “just a distraction,” it can sting. Because there’s an unspoken accusation in there: that taking 10 minutes to watch the sky means you don’t care enough about what’s happening on the ground. Reality is messier. You can be terrified about the climate and still want to stand in the shadow of the moon. You can volunteer, donate, vote – and also plan the perfect eclipse playlist. Life doesn’t come in tidy moral categories.

The astronomers I spoke to sounded almost defensive about the criticism. One of them paused, then said slowly:

“We study the eclipse because the sun is literally the source of our climate, our power, our weather. Calling that a distraction from ‘real problems’ misses the point. It’s the same problem, just zoomed all the way out.”

She pointed to three reasons this eclipse could be quietly powerful:

- Shared focus – for a few minutes, millions of people pay attention to the same thing without arguing.

- Reset of scale – you’re reminded you live on a rock in space, which makes some daily dramas feel a bit smaller.

- Gateway to action – curiosity about the sky often nudges people toward science, climate awareness, and voting for evidence‑based policies.

That doesn’t erase the danger of turning everything into a selfie moment. It just means the story doesn’t have to end with the last shadow.

What happens after the shadow moves on

When totality ends, something strange always happens. People blink, shuffle their feet, check their phones and start refreshing news apps, as if the regular world has been waiting impatiently on the other side. The crickets shut up. The birds remember their lines. Daylight snaps back, harsh and ordinary, like the house lights after a concert.

Yet for many, the feeling lingers. A quiet suspicion that the world is both more fragile and more generous than they’d allowed themselves to believe the day before. That the line between “real problem” and “real wonder” might be thinner than the moon’s edge against the sun.

The coming “longest eclipse of the century” will spark the same debates. Cities along the path will argue over traffic, emergency services, and tourism cash. Headlines will bounce between “historic celestial event” and “are we being distracted from the crises that matter?” Politicians will probably shoehorn it into their speeches.

You might stand in a field or on a balcony or in a cramped office parking lot. Beside you, someone will probably complain about the economy. Someone else will look up and gasp. You might feel nothing at all. Or you might feel a door in your brain crack open just a bit, letting in the wild idea that you’re part of something so much bigger, it barely fits into words.

*Maybe the real question isn’t whether the eclipse pulls us away from reality, but what kind of reality we walk back into once the sky goes bright again.*

If we treat it as a cosmic fireworks show, it’ll vanish as quickly as the last spark. If we treat it as a reminder – that our climate depends on that star, that our politics play out on this tiny spinning stage, that our time is more finite than we care to admit – then those seven minutes are not an escape at all.

They’re a mirror.

What we choose to see in it is still up to us.

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Longest eclipse of the century | Over 7 minutes of totality in some regions, with day briefly turning to night | Helps you decide whether to travel, plan, or simply step outside to witness it |

| Safety and spectacle can coexist | ISO eclipse glasses, indirect viewing methods, and local events | Lets you enjoy the wonder without risking your eyesight or your kids’ |

| Not just a distraction | Links between cosmic awe, climate awareness, and shared attention | Gives you a way to use the moment as reflection, not just entertainment |

FAQ:

- Question 1Is this really the longest total solar eclipse of the century?

- Answer 1Astronomers project that this eclipse will offer the longest duration of totality in the 21st century, with some points along the path experiencing more than 7 minutes of complete coverage. Most locations will see less, but still far more than a typical 1–3 minute event.

- Question 2Are ordinary sunglasses enough to watch the eclipse safely?

- Answer 2No. Regular sunglasses, even very dark ones, don’t block the intense solar radiation that can permanently damage your retina. You need certified eclipse glasses or solar filters that meet the ISO 12312-2 safety standard, or you should use indirect methods like a pinhole projector.

- Question 3Isn’t all this media hype just a distraction from real-world crises?

- Answer 3It can be, if the coverage stops at “pretty pictures in the sky.” It doesn’t have to be. Many scientists and educators use eclipses to talk about climate, energy, and our place on a fragile planet. The event can be both breathtaking and a gateway to bigger conversations.

- Question 4What’s the best way to actually experience the eclipse?

- Answer 4Try to get into the path of totality if you can. Arrive early, bring proper eye protection, water, and a way to take notes or record your feelings – not just videos. Watch the light, the animals, the temperature, and the faces around you. Share the moment with others; it’s more powerful when it’s collective.

- Question 5Will there be another chance like this in my lifetime?

- Answer 5There will be other eclipses, but one with this combination of duration, visibility, and global attention is rare. For many people, especially those who don’t travel long distances for astronomy events, this really may be a once‑in‑a‑lifetime wonder.